Lassen Sie sich von Istar mit unserer Erfahrung und unserem Know-how beim Start Ihres Projekts unterstützen!

Laden Sie Ihre Designdateien und Produktionsanforderungen hoch und wir melden uns innerhalb von 30 Minuten bei Ihnen!

Pure aluminum melts near 660 °C, but if you run a furnace, weld, or cast for a living you already know the real story is messier. The useful truth is this: you are never dealing with a single temperature, you are managing a window shaped by alloy chemistry, oxide, atmosphere, and the way heat moves through metal and brick.

Datasheets repeat the same value: 660.3 °C (1220.58 °F) for elemental aluminum in near-perfect purity. That figure is well established and consistent across handbooks and thermodynamic data sets, and it is the right anchor point if you need a clean reference. But commercial material rarely lives at that purity level, and plant equipment never operates under the neat conditions that produced that number in the lab.

Even stepping down from 99.999 % aluminum to “industrial pure” grades shifts behavior. As small additions of iron, silicon, and other residuals appear, the sharp melting point softens into a short range. For a 1100 series alloy with about 99 % aluminum, the effective melting interval already spreads roughly from the mid-640s to the mid-650s °C, not the textbook 660.3 °C. That is before you bring oxide skins, hydrogen, and refractory interfaces into the picture, all of which move your practical window again.

So the usual headline number is useful, but only as a baseline. What matters in day-to-day work is how quickly your grade leaves the fully solid state and how quickly it approaches fully liquid under your specific heating route.

If you work with alloys like 6061, 7075, or A356, you never see a clean “on/off” transition. You see a mushy zone. Below the solidus, the alloy behaves as a solid; above the liquidus, it flows as a true liquid; between those two, it is a mixture of solid and liquid in proportions that shift with every few degrees.

Typical data for wrought 6061 shows a solidus around 580–582 °C and a liquidus near 650–652 °C, depending on the exact composition and source. High-strength 7075 opens the window much lower, starting to melt around 477 °C and only fully liquid by roughly 635 °C. Common casting alloy A356 sits in between, with many datasheets quoting a melting range roughly from the mid-550s to around 610–615 °C.

Once you think in terms of solidus–liquidus rather than a single melting point, several things line up. Incipient melting during heat treatment stops being mysterious. Hot-short cracking in welding stops looking random. Grain boundary chemistry, segregated particles, and eutectic pools finally have a slot in the mental model.

The table below keeps the focus on numbers people actually use at the furnace or in process simulations, not just the ideal value for pure aluminum.

| Material / Alloy | Typical composition note | Melting point or range (°C) | Practical comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum, high-purity | 99.99 %+ Al | 660.3 | Baseline reference used in handbooks and phase diagrams. |

| Aluminum 1100 | ~99 % Al with Fe, Si residuals | 643–657 | Narrow range, still treated as “commercially pure”; good reminder that real products already show a range. |

| Aluminium 6061 | Al-Mg-Si wrought alloy | 582–652 | Wide mushy zone; critical for extrusion billet heating and avoiding incipient melting in solution treatment. |

| Aluminium 7075 | High-Zn Al-Zn-Mg-Cu | 477–635 | Very broad range; melting onset is low enough that overly aggressive heat treatment can cause local liquation. |

| Aluminum A356 | Al-Si-Mg casting alloy | 555–615 (typical range) | Comfortable casting window but easy to overheat if you chase higher fluidity without gas control. |

| Kupfer | Commercially pure | 1084–1085 | Useful contrast: significantly higher than aluminum, tighter melting interval, different oxidation behavior. |

| Carbon steel (plain) | Fe with C, Mn | 1425–1540 | Very high range; shows why aluminum furnaces and steel furnaces feel like different worlds. |

| Titan | Commercial purity | 1668 | Another reference point; structurally strong far above any temperature where aluminum is still solid. |

The exact values in your plant will slide slightly with chemistry, furnace calibration, and atmosphere, but the relative order and spread rarely change. Once you have this order in your head, choices about refractories, burner settings, and process limits get much simpler.

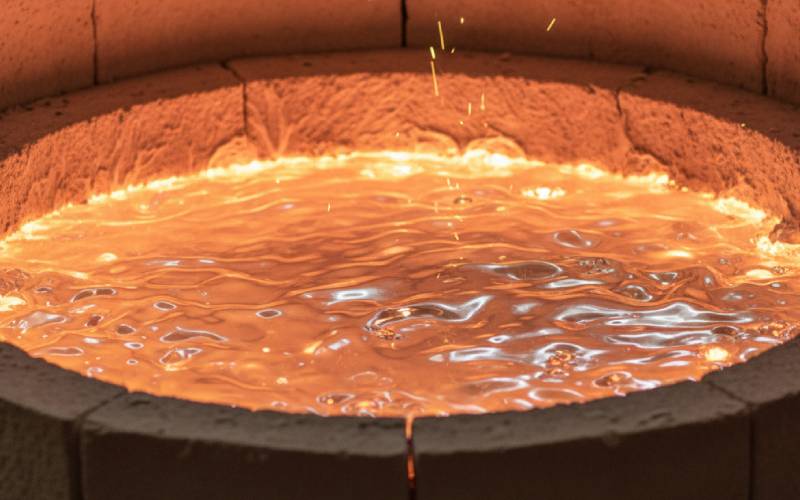

One persistent complication with aluminum is that the solid metal and its oxide do not share similar melting behavior at all. Metallic aluminum melts near 660 °C, but aluminum oxide sits near 2070 °C, solid and stubborn. So even when your charge is fully molten underneath, the surface can keep a dull, coherent skin that looks deceptively solid.

That skin thickens with time at temperature and with exposure to air or combustion products. It traps dross, it resists flow, and it is part of why simple “look through the sight glass” temperature guesses are so unreliable. You can be tens of degrees above liquidus and still see a sluggish, semi-solid crust.

The boiling point of aluminum is much higher again, on the order of 2467 °C. You will not see boiling aluminum in normal industrial practice, but that huge gap between melting and boiling matters for process safety. Vaporization is not how you lose metal; oxidation, splashing, and fume carryover are. Visual cues from steel practice, where color and spark behavior give some guidance, fail badly here because aluminum stays silvery right up to the point where it collapses.

Most introductory material on aluminum melting stops once the metal is liquid. The furnace, sadly, does not. Refractory linings see a different thermal and chemical world from the bath, and the melting behavior of aluminum dictates which zones suffer first.

In a typical fuel-fired or electric reverberatory furnace you can think about two broad zones. The upper zone is exposed mainly to combustion gases or hot air; the lower zone is in direct contact with molten aluminum and slag. The interface between them, often called a bellyband, sees both sets of conditions and tends to be a hotspot for wear.

Because aluminum melts at a modest temperature compared with steel, there is a temptation to treat any generic high-alumina brick as “good enough”. The problem is that molten aluminum is highly reactive with many oxide refractories. Slight overheat to gain fluidity, or long hold times just above liquidus, can accelerate corundum growth, metal penetration, and spalling. Choosing linings with suitable additives and glazing behavior is as much a response to aluminum’s melting window as it is to the nominal peak furnace temperature.

Foundry work usually talks less about exact melting point and more about superheat: how many degrees above liquidus you actually run your ladle or furnace. For aluminum alloys with a roughly 60–100 °C mushy zone, that choice sets the balance between fluidity, gas pick-up, and lining damage.

With A356, for example, a melt range in the 555–615 °C region gives you room to pick a superheat that fills thin sections but does not spend unnecessary time far above liquidus. Too cold, and the leading edge of the stream hits the mold in a semi-solid state, freezing before it can vent. Too hot, and you gain fluidity but invite hydrogen absorption and oxide formation, which you then chase downstream with more flux and more scrap.

The same logic extends to degassing, filtering, and holding. Every minute spent at the upper end of the superheat range expands the oxide and dross layer and gives hydrogen more time to enter solution. When people say an alloy is “forgiving”, they often mean the casting still works even when the chosen superheat is not well matched to the true liquidus.

Solution heat treatment schedules for aluminum alloys often run only a few tens of degrees below solidus. That is by design; you want enough thermal energy to dissolve strengthening phases quickly without triggering localized melting. For 6061, that might mean a furnace setpoint in the mid-500s °C, safely under a solidus near 580 °C. For 7075, the margin is smaller, because segregation pushes local melting onset lower than the bulk solidus number suggests.

Microsegregation during solidification leaves solute-rich regions at grain boundaries and around eutectic particles. Under aggressive solution treatments, those pockets can partially liquify even though the bulk alloy is nominally below solidus. The result shows up as “mottled” surfaces, loss of sharp edges, or complete part failure during quench. The root cause, though, is still that mismatch between a single handbook melting point and the real, spatially varied melting behavior of the alloy.

In practice, careful ramp rates, tight furnace calibration, and the use of sacrificial test coupons let you approach the useful limit without crossing it. The people who get this wrong usually are not missing data; they are trusting the single melting point number more than the process deserves.

Arc welding and laser welding of aluminum add another twist. Instead of heating a whole casting or billet into the mushy range, you create a small, intense pool that transitions from ambient to above liquidus over a few millimetres.

Here, the lower end of the melting range is especially important. Alloys like 7xxx series, with early-onset melting around 477 °C, are more prone to liquation cracking in the heat-affected zone than 5xxx or 6xxx alloys. If filler metal composition and heat input are not tuned to that behavior, cracks open as the partially melted grain boundaries try to carry stress while solidifying.

Preheating, travel speed, and joint design all become knobs for controlling how long those regions sit between solidus and liquidus. Again the physics is simple, but the operational feel develops only when you stop thinking of “melting point” as a single step and start seeing it as a range over which the structure changes rapidly.

Laboratory data for aluminum melting come from several methods. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) measure the heat absorbed as a sample warms through its melting range. That is how many of the solidus and liquidus values in datasheets are obtained.

At the other end of the scale, atomistic simulations now track crystal and liquid phases directly to estimate melting temperatures. Recent work using coexistence methods for aluminum reports melting around 858 K within a given interatomic model, illustrating how sensitive predicted values can be to the assumptions built into the simulation. Those numbers are not meant to replace the handbook value; they help researchers tune potentials and understand how defects and interfaces shift behavior at the nanoscale.

For engineers, the takeaway is simpler. Ask which definition of “melting point” a dataset uses. Is it the onset of melting, peak heat flow, complete melting, or some operational criterion like “viscosity below X”? Different tests, all valid in context, can give slightly different answers for the same alloy.

If you already know the official numbers, what else actually helps on the floor or in design reviews. A few patterns tend to hold across plants and sectors.

First, always have the solidus for your current alloy in front of you, not just the liquidus or the pure aluminum reference. That single line on a setup sheet stops a surprising number of heat-treatment mistakes.

Second, think and communicate in terms of “degrees above liquidus” when you talk about casting and holding, not just in absolute furnace setpoints. It keeps conversations honest when different shifts run slightly different temperature offsets.

Third, when chasing a defect, look for places where the local thermal history might have entered the mushy range even if the bulk temperature log looks safe. Slow-responding thermocouples, hot spots in the burner pattern, or unusual part geometry all conspire to create local pockets of trouble.

Finally, remember that every refractory choice, flux practice, and alloy change tweaks your practical melting window. None of those decisions are separate; they are all small nudges to the same underlying temperature range.

The precise melting point of aluminum is real, measurable, and deeply studied. The way your alloy melts in your furnace is a different, more complicated thing. Once you accept that you are always working with a range instead of a single point, decisions across casting, welding, and heat treatment start to line up in a cleaner way.

Treat the handbook value as a compass heading. Then tune your actual process window around solidus, liquidus, oxide behavior, and the limits of your equipment. That is where the real control over aluminum melting lives.