Let Istar help you get started on your project with our experience and know-how!

Upload your design files and production requirements and we will get back to you within 30 minutes!

If you need one general-purpose aluminum grade that simply works across structures, frames, and machined parts without chasing extremes, 6061 is usually the answer.

Designers usually land on 6061 not because it is the strongest alloy, or the easiest to form, but because it sits in a useful middle ground. Strength in the mid-to-high range for aluminum, decent fatigue behaviour, good weldability, acceptable corrosion resistance, and availability in almost every product form from thin sheet to chunky plate and complex extrusions.

You can build aircraft brackets, marine fittings, automotive fixtures, machine frames, and consumer hardware from the same alloy family and keep purchasing, machining, welding, and finishing workflows under control. That consistency is a big part of its real value, much more than any single number on the datasheet.

6061 is a heat-treatable 6xxx series aluminum alloy. Magnesium and silicon are the main alloying elements; together they form Mg₂Si precipitates during heat treatment, which give the alloy its strength.

Compared with 6063, 6061 usually carries slightly higher levels of silicon, copper, chromium, and sometimes iron, which is one reason it wins on strength but loses a bit on surface finish and formability.

You normally see 6061 in tempers like O (annealed), T4, T6 and T651. All of them are chemically the same alloy; only the heat treatment and mechanical history differ.

Design decisions tend to be controlled by three clusters of behaviour: static strength and stiffness, fatigue, and what happens after welding or forming.

Mechanically, 6061 sits comfortably in the “strong enough for many structural jobs” bracket. Typical room-temperature values for common tempers look roughly like this:

| Temper | Approx. tensile strength (MPa) | Approx. yield strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) | Typical use pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6061-O | ~120–130 | ~55–70 | 18–25 | Deep forming, tight bends, parts to be heat-treated later |

| 6061-T4 | ~240 | ~140–150 | 12–17 | Intermediate strength, better formability than T6 |

| 6061-T6 | ~300–320 | ~270–280 | 8–12 | General structural, machined parts, extrusions |

| 6061-T651 | Similar to T6 | Similar to T6 | 8–12 | Plate stock where residual stress control matters |

Elastic modulus sits near 69 GPa regardless of temper, so stiffness is basically set by geometry, not heat treatment.

Fatigue strength is modest compared with high-strength steels, but it is reasonable for aluminum, usually quoted around 95–100 MPa for rotating bending at high cycle counts. Surface finish, stress concentrators, and welds will move that number around far more than the datasheet alone suggests.

6061 has “good, not heroic” corrosion resistance. In quiet indoor environments it behaves very well. In mildly corrosive outdoor conditions and many marine atmospheres, bare 6061 still performs acceptably, especially in T6 temper. Alloys like 6063 or 5xxx series grades often edge it out when you push into more aggressive chloride exposure or when you need outstanding anodized surface quality.

For submerged or splash-zone marine use, engineers often pair 6061 with appropriate coatings or anodizing, select fasteners carefully, control galvanic couples, and keep weld geometry conservative. That combination is why you see the alloy in marine fittings, small boat structures and similar components without constant drama.

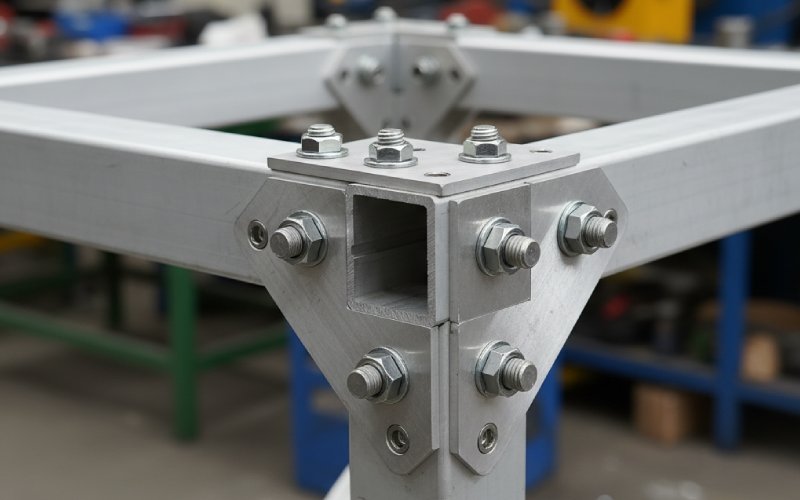

One of the real reasons 6061 is loved in fabrication shops: it MIG and TIG welds reliably. Filler selection (such as 5356 or 4043) and joint preparation still matter, but in terms of weldability within aluminum alloys, this one is on the friendly side.

The trade-off appears right next to the weld bead. In T6 or T651, the heat-affected zone locally overages or re-solutions the strengthening precipitates, so the yield strength near the weld drops toward something closer to T4. You get a strong parent material, softer zone beside the weld, and then the weld metal itself with its own properties. Design calculations that pretend the whole joint is “T6” do not age well.

In structural work, this often leads to using thicker sections near connections, spreading loads over longer welds, or heat treating entire assemblies when that is economically viable. Many design failures with 6061 are not about the alloy at all; they come from underestimating what the heat-affected zone does to your safety margins.

Formability is strongly temper-dependent. O and T4 bend cleanly, even to fairly tight radii. T6 bends need respect: larger bend radii, attention to grain direction, and realistic expectations about cracking risk.

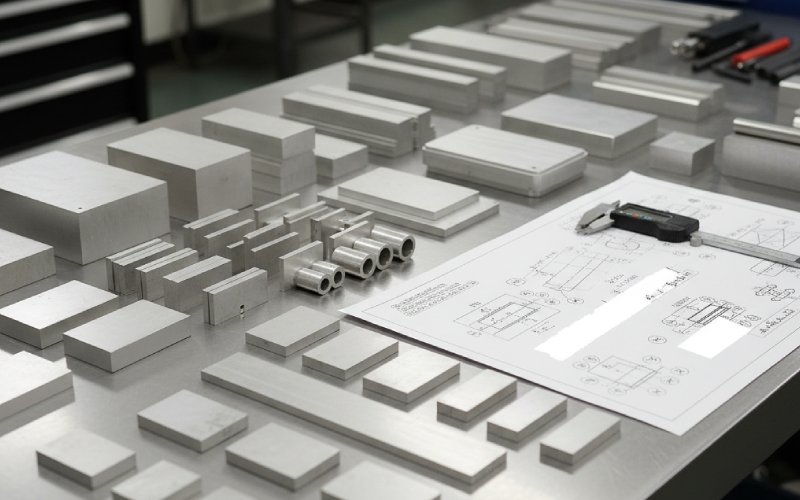

Machinability is usually rated as “good”. Chip control is predictable, tools last reasonably long, and surface finishes are fine for structural and many cosmetic applications, especially with sharp tools and sensible cutting parameters. Compared with softer alloys like 6063, 6061 can deliver slightly better dimensional stability in heavily machined sections because of its higher strength and the availability of stress-relieved plate (T651).

Many drawings default to “6061-T6” in a single line, and that is where problems begin. It is more useful to think in terms of the process route.

When you need deep forming or tight bending followed by heat treatment, starting with O or T4 and then aging to T6 after forming is the cleaner path. Thin sheet parts, brackets with complex geometry, or products with deep draws often follow this route in larger production volumes.

For extrusions and general structural shapes that will not see heavy forming after delivery, T6 is the workhorse. You cut, machine, weld if required (accepting the softened heat-affected zones), assemble, finish. For plate stock that needs extensive machining, T651 is often preferred because the stretching step used to relieve residual stresses reduces distortion during machining.

The less obvious choice is to leave some parts in T4. If you have components where ductility and toughness matter more than peak yield strength, or you expect complex loading with stress concentrations, T4 can give a more forgiving failure mode. Many engineers reach for T6 by habit when T4 would have given a more robust design against real-world abuse.

Because of its strength-to-weight ratio and weldability, 6061 shows up in a wide range of aerospace and aviation hardware, particularly in general aviation and homebuilt aircraft: ribs, brackets, non-critical structural members, and fittings that must be machinable and weldable yet reasonably light.

In transport and mobility, you see it in vehicle chassis components, suspension links, wheels, fixtures, and subframes. It offers enough strength for these jobs without the more demanding processing and corrosion management that 2xxx or 7xxx high-strength alloys require.

Marine hardware is another common domain: masts, small boat structures, gangways, docks, marine fittings, and yacht components. Here the balance is between acceptable corrosion behaviour, reasonable strength, and the ability to weld and repair on site. 5xxx series alloys are often preferred for the most aggressive saltwater service, but 6061 still occupies a large space in fittings and secondary structures.

Then there is the broad category of frames and fixtures: machine bases, inspection fixtures, jigs, camera and optical mounts, sports equipment like bicycle frames, archery risers, and a long list of consumer products. The intersection of machinability, stability, and the option to anodize makes 6061 an easy choice for teams that want to prototype and then move into production with minimal redesign.

High-pressure gas cylinders and scuba tanks have also been produced from 6061, usually in specific tempers and with tightly controlled processing routes, taking advantage of the alloy’s combination of strength and ductility.

The first comparison nearly everyone makes is with 6063. Both are 6xxx series, both contain magnesium and silicon, both can be heat treated. 6063 is softer, extrudes more easily, and provides a better surface finish and anodizing response for architectural and decorative profiles. 6061 usually beats it on yield strength and fatigue strength, which is why you see 6061 in more heavily loaded structural roles while 6063 fills architectural window frames, trim, and intricate decorative shapes.

Compared with 2xxx and 7xxx aerospace alloys like 2024 and 7075, 6061 loses on absolute strength but wins on corrosion resistance and weldability. Alloys like 2024 often need cladding for corrosion protection and are rarely welded in critical structures; 6061 is more forgiving in mixed-environment applications where maintenance will not always be perfect.

Relative to 5xxx series alloys such as 5083, which excel in marine and cryogenic service, 6061 offers greater heat-treatable strength but can be more susceptible to certain corrosion issues if used unwisely in some marine environments or at elevated temperatures under stress. This is why you will often see 5083 in ship hulls and 6061 in fittings, masts, and secondary structures.

For designers, the practical rule of thumb often becomes: if finish quality and complex extrusions dominate, 6063 goes to the front of the queue; if structural strength, machined details, and decent weldability dominate, 6061 takes the lead.

Extrusion is a major product form for 6061. You can ask for reasonably complex shapes, but very deep, thin fins or extremely sharp corners will either drive up cost or simply be rejected by the mill. There is also a limit to how tight a cross-section can be and still fill properly in T6. Knowing this, experienced designers simplify profiles and push truly intricate shapes toward alloys and processes better suited for that job.

Bending requirements push you back to temper selection. If a part must be bent after machining, switching from T6 to T4 for that operation and then artificially aging to T6 afterwards may save scrap and rework. For one-off or low-volume jobs, accepting a slightly larger bend radius and aligning bends perpendicular to the extrusion grain are often simpler fixes.

Weld design is another area where 6061 rewards respect. You cannot assume full-strength fillet welds in T6 material without accounting for the softened heat-affected zones; the weakest link moves away from the weld metal and into the adjacent parent material. That shifts where cracks start and how they grow. Longer joints, double-sided welds, and thicker sections near connections are common countermeasures.

Residual stress and distortion in thick plate can be surprisingly influential. Using T651 plate, with its stress-relief stretch, is a straightforward way to keep machined components flatter and reduce the number of straightening operations after machining.

From a finishing perspective, 6061 anodizes well, though not always with the ultra-smooth cosmetic finish that 6063 can deliver. For functional anodizing (hardcoat, corrosion protection, wear surfaces), 6061 is widely used; for architectural finishes where visual perfection is the main concern, designers often step sideways to 6063 or specially controlled 6xxx variants.

If you are deciding whether 6061 is appropriate for a new part, the thought process usually goes something like this, even if you never write it down.

You check the required strength: if your loads are modest and stiffness is controlled by geometry, 6061-T6 or T651 will usually meet the numbers with helpful margins. If you are chasing extremely high strength-to-weight, you start questioning whether a high-strength 7xxx alloy, a steel, or a composite is more justified.

You look at fabrication routes: if you need welding, 6061 scores highly, as long as you design for softened zones and possibly post-weld heat treatment on critical structures. If you need deep forming after delivery, a softer alloy or a different temper within 6061 can make more sense.

You consider the environment: indoor dry, general outdoor, marine, chemically exposed. For many everyday environments, 6061 is perfectly acceptable with simple coatings or anodizing. For aggressive marine or chemical exposure, specialist 5xxx alloys or carefully finished 6xxx grades may be better.

And then you consider logistics: stock availability, forms, local supplier capability. One of 6061’s biggest real advantages is simply that mills, service centres, and fabricators around the world are set up for it. You can usually get the bar, plate, sheet, or extrusion you need without a supply-chain adventure, which often matters more than a few percent of strength on paper.

6061 is not the most exotic alloy in the catalog and that is precisely why it is so widely used. It gives engineers a reliable blend of strength, weldability, machinability, and corrosion resistance, with a long track record in aerospace, marine, automotive, structural, and consumer applications.

If you pick the temper sensibly, respect the heat-affected zones in welded joints, and match finishing and protection to the environment, 6061 tends to behave predictably. For many projects, that quiet predictability is exactly what you want from a material: it lets you focus your design effort on geometry, interfaces, and manufacturing flow, while the alloy just does its job in the background.