Let Istar help you get started on your project with our experience and know-how!

Upload your design files and production requirements and we will get back to you within 30 minutes!

Most extrusion profiles end up in 6061. You only reach for 7075 when the loads are high, the geometry is simple, and you are ready to pay in money, process difficulty, and coating effort for more strength than 6061 can give.

If you have already read the alloy datasheets, you know the usual line: 6061 is the general-purpose workhorse with good corrosion resistance and weldability; 7075 is the high-strength option with poorer corrosion performance and lower weldability.

For extrusion profiles, the story shifts slightly. The press operator, the die life, the scrap rate, and the surface finish all start to matter as much as the pure mechanical values. Most online comparisons stop at yield strength and cost. They rarely talk about how 7075 behaves when you try to push a thin-fin profile at production speed, or what happens to your tolerance stack when a high-strength extrusion springs during ageing.

So this is not a tutorial on what 6xxx or 7xxx alloys are. It is a design conversation about where 6061 and 7075 make sense as extrusion materials, and where they quietly ruin your day.

You already know the general trend: 7075-T6 is roughly “twice as strong” as 6061-T6 in tension. Depending on source and temper, typical values sit around the numbers below.

| Property (T6, typical) | 6061-T6 | 7075-T6 | Practical note for extrusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultimate tensile strength, MPa | ~310 | ~560 | 7075 lets you shrink section size for the same static load, if buckling and stiffness allow. |

| Yield strength, MPa | ~270 | ~480–500 | Design-by-yield parts that are stress-driven, not stiffness-driven, are where 7075 has a clear role. |

| Fatigue strength (rotating bending), MPa | ~95–100 | ~150–160 | Under high-cycle loading (bike suspensions, aerospace fittings), 7075 can support similar life at smaller cross-sections. |

| Brinell hardness | ~90–95 | ~140–150 | 7075 keeps surfaces harder against wear and indentation but also punishes cutting tools. |

| Density, g/cm³ | ~2.70 | ~2.81 | Weight difference is modest; strength-to-weight, not density, is why people pick 7075. |

These numbers alone can be misleading. They say nothing about whether the extrusion can even be produced at scale. An “ideal” cross-section that depends on 7075 strength is useless if it tears, twists, or costs triple in press time.

Most commercial extrusion presses are tuned around 6xxx alloys. They know 6063 and 6061 by muscle memory. 7xxx alloys, including 7075, run slower, at tighter temperature windows, and usually with simpler dies.

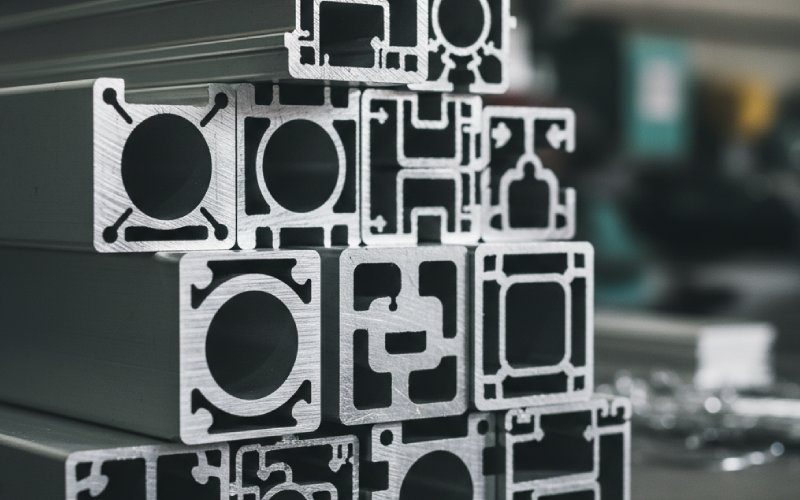

Because of that, 6061 tends to accept more ambitious shapes: deeper hollows, more pockets, thinner walls, sharper ribs. It is not that 7075 cannot be extruded; it is that it resists flow more, so complex dies push you into higher pressures, uneven metal flow, and higher risk of surface defects. Many extruders will quote you, but they silently widen the minimum wall thickness, shorten fin lengths, or refuse geometries they happily run in 6061.

If you are designing a profile before talking to a press shop, assume this rough pattern: if your profile already looks a bit like a heat sink, or a complicated T-slot framing shape with multiple internal cavities, it is almost always a 6061 job. 7075 is more commonly used for bars, tubes, channels, and simpler shapes where the metal flow is predictable.

Process window tightness also shows up in consistency. 6061 forgives small variations in extrusion speed and quench; 7075 punishes them with dimensional drift and more scatter in mechanical properties along the length. If you care about long, straight profiles for sliding systems or precision assemblies, that extra scatter is part of the decision, not an afterthought.

Strength is only one axis. Many extrusion profiles are stiffness-driven, not strength-driven. Think machine guarding, conveyor frames, fixture rails, door frames. You hit deflection limits long before the stress in 6061 approaches yield. For these, upgrading to 7075 does not let you use much smaller sections; the section modulus dominates, not the allowable stress.

On the other hand, some geometries really are stress-driven. Examples include compact mounting ears with short edge distances, thin-wall tubes in bending, or heavily loaded lugs. In those, 7075 lets you keep a low profile or stay within a tight envelope, where 6061 would require thicker walls that do not fit the system. This is why 7075 extrusions show up in aerospace fittings, some high-end bicycle parts, and performance suspension components.

The trick is to be honest: if you run a quick check using 6061 properties and your margins are already comfortable, 7075 adds complexity for no clear benefit. The gap in raw strength is tempting, but using it where stiffness rules gives you cost without real engineering gain.

You already know the headline: 6061 has better general corrosion resistance, 7075 is more prone to stress corrosion and often needs protective coatings or cladding.

For extrusion profiles, that has several quiet consequences. Outdoor structures, marine or coastal environments, and profiles that will be anodized clear or lightly dyed tend to favor 6061. Its oxide layer behaves predictably and gives a stable, uniform appearance, which is handy when several batches must match visually.

7075 can be anodized, but the color and gloss often differ from 6061 under the same process. Even among 7xxx alloys the tone can shift, so using 7075 extrusions mixed with 6061 accessories in a visible assembly makes color matching harder. In more aggressive environments, 7075 often ends up painted, hard-anodized with specific seal chemistry, or otherwise coated.

So if your extrusions are structural but exposed and visible, and you care about long-term surface stability more than absolute strength, 6061 is usually more calm to live with.

From a joining standpoint, 6061 wins on simplicity. It is widely considered weldable with common processes, and post-weld properties are well documented. For extrusion profiles that will be cut, framed, and welded into assemblies, this matters more than the slight property advantage of some alternative 6xxx alloys.

7075 is different. It is generally classified as not readily weldable for structural use due to hot cracking and loss of strength in the heat-affected zone. Where 7075 extrusions are used, joints are typically mechanical or bolted, or in some cases bonded. This pushes you toward thicker joint areas, larger overlapping regions, and tighter control of fastener patterns, which again eats into the strength advantage if the geometry grows.

Machining is the other part of the story. Both alloys machine well, but 6061 is usually easier to cut and form, with longer tool life and less tendency to chatter at typical feeds and speeds. 7075’s higher hardness gives cleaner, crisper edges and good dimensional stability under cutting loads but at the cost of more aggressive tool wear and a bit more care with heat input.

If your extruded profile is only the raw stock for heavy CNC work, and the part is strength-critical, 7075 can be reasonable. If the machining is light and mostly for slots, holes, and trimming, 6061 is usually more economical overall.

Most of the extrusion supply chain is built around 6xxx alloys. 6063 and 6061 dominate standard dies, stocking programs, and off-the-shelf system profiles. That means lead times, MOQs, and per-kilogram prices for 6061 are usually more favorable. You can often find existing dies close to what you need, or at least suppliers who are comfortable developing a new shape.

7075 is a narrower market. Fewer presses like to run it, fewer have experience with complex shapes, and minimum quantities tend to be higher. The alloy price itself is higher, and the slower extrusion speed and tighter scrap tolerances add more cost on top.

So when you choose 7075, you are not just paying for the ingot. You are paying in quoting friction, fewer supplier options, and less flexibility if you need a small engineering change late in the project.

Seen across industry, some patterns repeat. 6061 extrusions are everywhere: industrial framing, machine bases, conveyor systems, moderate-load structural members in vehicles, architectural components, fixtures, consumer products. Many of these parts do not stress the alloy anywhere near its limit. The attraction is consistency, corrosion resistance, easy welding, and a huge number of compatible accessories.

7075 extrusions show up where designers truly trade process difficulty for performance: aircraft fittings and stiffeners, high-end bicycle and motorsport parts, some defense components, and niche sports equipment. Here, loads are high, stiffness envelopes are tight, and the part count is low enough that a more complex supply chain can still make sense.

If your application resembles the first group more than the second, the answer usually leans toward 6061 unless there is a specific, quantified reason not to.

Start with your load case, but do it twice. First, size your profile in 6061-T6 based on both stiffness and strength. If all critical locations see stress well below 6061 yield and deflection is acceptable, you already have your answer. A clean margin on 6061 usually beats the complexity of moving to 7075.

If you find one or two regions where 6061 is marginal, try design changes before changing alloy. Minor tweaks to rib thickness, radius, or local section modulus often recover more capacity than stepping up to 7075 would, without touching materials or suppliers.

Only if the geometry is already constrained and your analysis still needs significantly higher allowable stress or fatigue strength does 7075 start making sense. At that point, you talk early with extrusion houses that already run 7xxx alloys, confirm feasible wall thickness and die complexity, and accept that coating, joining strategy, and cost will all adjust around that choice.

For extrusion profiles, 6061 is the default: good corrosion resistance, good weldability, decent strength, friendly extrusion behavior, broad supplier support. 7075 is the specialist: higher static and fatigue strength, harder surfaces, but with weaker corrosion resistance, limited weldability, more demanding processing, and narrower availability.

Most projects do not truly need 7075 once the geometry is cleaned up and stiffness constraints are understood. When they do, it is usually obvious from the requirements: extreme load, tight space, high-cycle fatigue, and acceptance of extra process constraints.

If you design with that mindset, you end up with extrusions that match both the mechanical need and the industrial reality, rather than just the strongest alloy on the datasheet.