Let Istar help you get started on your project with our experience and know-how!

Upload your design files and production requirements and we will get back to you within 30 minutes!

You almost never choose between a bearing and a bushing because of friction alone. You choose because of how you expect the system to age, misbehave, and occasionally be abused.

If you read vendor guides, you get neat tables: bushings for high load and low speed, rolling bearings for precision and high speed. True, but that’s the kindergarten version.

In real projects, the choice is usually about what happens in year three when the operator stops greasing the joint, dust gets past that seal you “optimized,” or the supplier quietly swaps materials. At that point, you find out whether your decision was about the whole system or just about a component drawing.

Most comparison articles stop at a list of pros and cons and a couple of fan lifetime graphs.Let’s treat bearing vs. bushing as a design strategy, not a multiple-choice quiz.

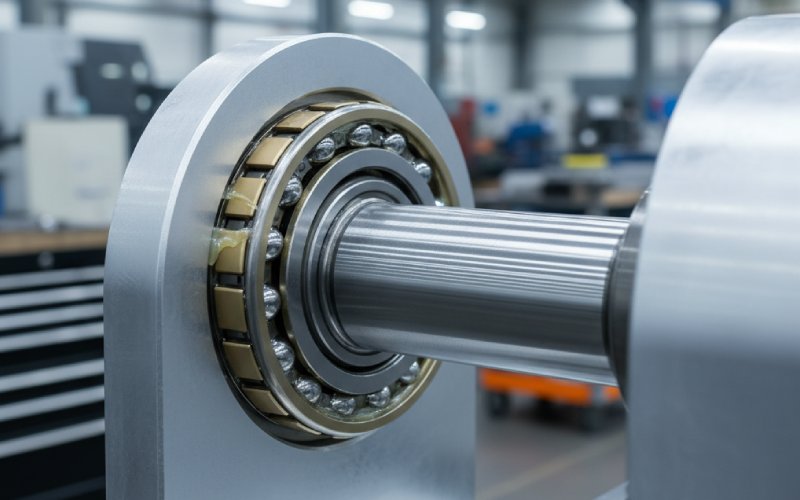

Rolling bearings give you low friction, predictable stiffness curves, and tight positional behavior. Great if you care about microns and efficiency. They pay you back when you run them near their rated speeds for long stretches and when the load direction is well-behaved.

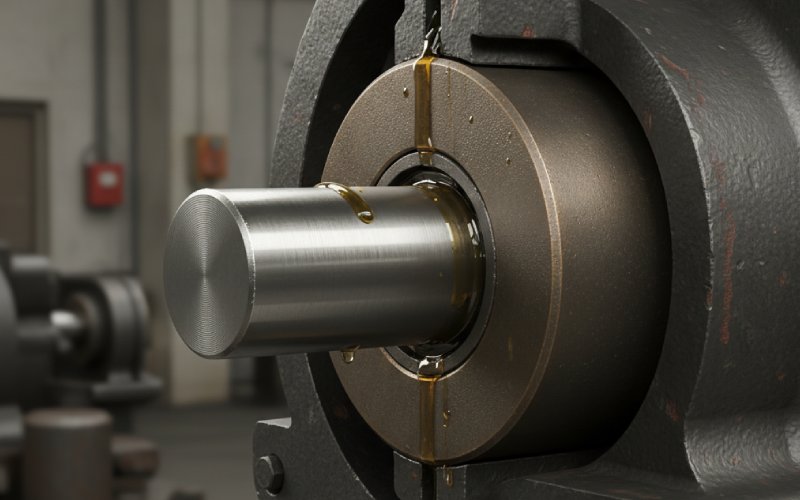

Bushings trade all of that for simplicity and tolerance for chaos. A sleeve in bronze or a polymer composite will quietly accept shock, dirt, rough mounting, and the occasional misaligned shaft, as long as you respect a few unglamorous basics: load per unit area, sliding speed, and lubrication regime. Plain bearings are literally defined by having no rolling elements, which is exactly why they survive in ugly environments.

If you think of rolling bearings as instruments and bushings as fuses, your decisions get cleaner.

Here is a compact view that assumes you already know the textbook theory and nomenclature:

| Design axis | Rolling bearings (ball / roller) | Bushings / plain bearings |

|---|---|---|

| Typical speed regime | Moderate to very high; friction stays low once spinning | Low to moderate; high sliding speeds demand careful PV and lubrication control |

| Load character | Excellent for steady radial and defined axial loads | Comfortable with high static load, oscillation, and shock |

| Misalignment tolerance | Limited; misalignment eats life fast | Often more forgiving, especially with compliant or split designs |

| Contamination and dirt | Sensitive; particles bruise raceways and rolling elements | Better tolerance with robust materials and generous clearances |

| Noise and vibration | Can be quiet but transmits discrete vibration signatures | Often better damping; “dead” feel can be useful |

| Start–stop and oscillating motion | Not ideal; micro-slip and false brinelling issues | Suited to short strokes and small oscillation angles |

| Mounting sensitivity | High; press fits, shoulder heights, and alignment matter a lot | Lower, though bad fits still cause uneven wear |

| Lubrication style | Grease or oil with focused sealing strategy | From dry/self-lubricating to boundary and full-film options |

| Cost, initial | Higher unit price, especially for precision classes | Usually cheaper per part, especially in simple geometries |

| Cost, long term | Favorable when life targets and maintenance are realistic | Favorable when access is poor or replacement must be extremely simple |

| Tolerance for abuse | Poor once overloaded or contaminated | Better, up to a point; then they fail in a very visible way |

| Supply chain complexity | Standardized part numbers, many equivalents | Can be custom geometry or material; sometimes one small supplier defines the project |

This table still hides the real decision, but at least it aligns more with how things fail in the field than how they look in catalogs. Comparisons like this mirror what you see in industrial selection guides, but with more emphasis on failure behaviors rather than only nominal performance numbers.

Rolling bearings look like the “premium” choice, so people install them in places where bushings would have been calmer and cheaper. Some examples appear again and again.

Short-stroke oscillation, like in many linkages. The ball or roller never rotates a full turn. It just rocks in place and chews a tiny zone in the raceway. Over time, that zone pits or wears; the bearing looks new everywhere else, but the application is finished. A bushing in a decent material would simply polish a band and keep going.

Dirty or wet environments that nobody will truly seal. Think agricultural implements, construction equipment, or exposed hinges on heavy machinery. Sliding plain bearings with the right material pair and clearances handle embedded particles and even some corrosion without catastrophic behavior, while rolling elements develop spalls and chatter that you hear across the yard.

Joints that see big impact. Bushings can spread force over an area and absorb shock through material compliance. A rolling bearing will localize contact stress, which is fine at design loads, less fine when a driver drops a bucket too hard or a press runs slightly out of timing for months.

Ultra-slow motion. At very low speeds, lubrication regimes are often boundary dominated anyway. The rolling bearing’s theoretical friction advantage gets small, but the cost and complexity remain large. A well-chosen plain bearing can accept the same duty with almost trivial geometry.

In all those cases, it’s not that the rolling bearing fails instantly; it just fails in non-obvious ways that hide during short tests.

The reverse mistake is more subtle. Someone sees “simple” and “cheap” and fills an entire design with bushings, then runs them well beyond their comfort zone.

High speed and long life in a hot environment is exactly where rolling bearings earn their place. The classic cooling-fan data show orders of magnitude differences in L10 life between ball and sleeve solutions as temperature rises and speed stays high. You can push bushings there, but it becomes a lubrication and thermal-management project, not a component choice.

Any system that has to maintain tight running accuracy over a long period, under varying load, often leans toward rolling bearings. Linear guides, precision spindles, gearbox shafts, even many automotive rotating joints: in all of these, consistent stiffness and low hysteresis matter more than the philosophical appeal of simplicity.

There is also the invisible overhead. A custom bushing with a specific composite, precise ID, and machined grooves for oil can look inexpensive on a drawing. But if the supplier changes resin, or your shop loses process control on the housing bore, you inherit a lifetime of tiny variations that no one traces back to that choice. A standard rolling bearing, for all its complexity, arrives with a known tolerance stack and verification path.

Official documentation goes deep into alloys, polymers, and surface treatments. You already know the usual suspects: bronze, PTFE-lined, sintered, stainless, and so on. The interesting decisions sit one level up.

First, decide which part you are willing to sacrifice. Bushings make this explicit: they are the wear item, meant to give their life to protect the shaft and housing. Rolling bearings are similar in theory, but in practice people treat them as “fit and forget,” then get surprised when shaft hardness or surface finish quietly dominates their life.

Second, decide who owns lubrication. If maintenance owns it, you can choose designs that depend on periodic grease or oil. If nobody realistically owns it, you are designing for sealed bearings or solid-lubricant bushings and whatever mixed regime they run in. That choice often decides between a sealed rolling bearing and a dry or impregnated plain bearing before you even touch the catalog.

Third, consider thermal mismatches. A polymer bushing in a hot metallic housing will grow differently and change clearance in ways a drawing doesn’t show. A bearing ring fitted into a thin housing can distort the race and cut its actual life dramatically. This is less glamorous than dynamic coefficients, but it tends to decide whether your prototype behaves like your spreadsheet.

Misalignment is one of the most common silent killers. A rolling bearing can tolerate a small angle, but beyond that it works hard to tell you it is unhappy: edge loading, local stress, weird wear patterns. Self-aligning constructions soften this, but at a price and with some trade in stiffness.

Bushings handle misalignment differently. With suitable length-to-diameter ratios and clearances, they redistribute contact and live with crooked assemblies, at least to a limit. Composite or split bushings offer some compliance that can absorb mounting error instead of concentrating it. Many OEM guides highlight this as a key advantage in heavy hinges and slow rotating joints.

The logic is slightly odd: the component that is crudest in appearance often gives the highest forgiveness to assembly mistakes, while the precisely ground bearing punishes you for every micron of misalignment. That tension is useful. It tells you where to spend machining budget and where to allow the joint to be crude and honest.

Life formulas for rolling bearings look very comforting: L10 equations, dynamic load ratings, reliability factors. Plain bearings have their own vocabulary: PV limits, film thickness ratios, contact pressures. Both sets of numbers promise clarity. Reality is less tidy.

For rolling bearings, most modern references note that contamination and mounting errors usually dominate life far more than catalog load ratings, especially in industrial and off-highway applications. That means your carefully computed L10 often just confirms what the cleanliness and assembly plan already decided.

For bushings, “life” usually collapses to a wear rate and a threshold of acceptable clearance or vibration. The underlying physics can be modeled, but in many projects people rely on dimensioned experience: “this geometry, in this material, survived in that previous machine.” Not elegant, but honest.

If you treat the calculations as gates instead of guarantees, the choice between bearing and bushing becomes more grounded. Pass the math, then ask how the user will actually treat the joint.

Before locking anything into your BOM, sit with the system and, almost literally, talk to it. Not in a poetic way; more like an interrogation.

How often will this joint move, really, over a day, over a year. Is motion continuous, or mostly parked with rare events. When it moves, is it smooth rotation or choppy oscillation. What actually happens when seals fail or someone forgets lubrication; does the machine stop, or does it limp along for months.

How dirty is the environment, genuinely, not in the brochure photo. What particle sizes, what fluids, what cleaning practices. Who installs the parts and with what tooling. Will anyone measure bores or shaft runout on the shop floor, or will components just be “pressed until it looks right.”

What is more expensive: slightly higher friction every day, or one catastrophic bearing failure in peak season. Is it easier to swap cheap bushings on site or to replace a precision bearing assembly in a workshop with correct fixtures.

As you answer those, you usually feel the design lean one way. That lean is more trustworthy than a pros-and-cons paragraph from a catalog.

“Bearing vs. bushing” sounds like a binary, but in practice it’s a question about risk distribution. Rolling bearings push risk into contamination control, alignment, and long-term lubrication quality. Bushings push it into wear rates, material choice, and the honesty of your clearances.

If you treat each joint as a specific contract between physics, maintenance, and cost, the choice stops being mysterious. You already know the theory; the useful step now is to map that theory onto the exact ways your machine will be misused, ignored, serviced, and occasionally pushed past its limits. That is where the right answer usually lives.